Sharing the Instrument – MIDI Sprout (2014-2016)

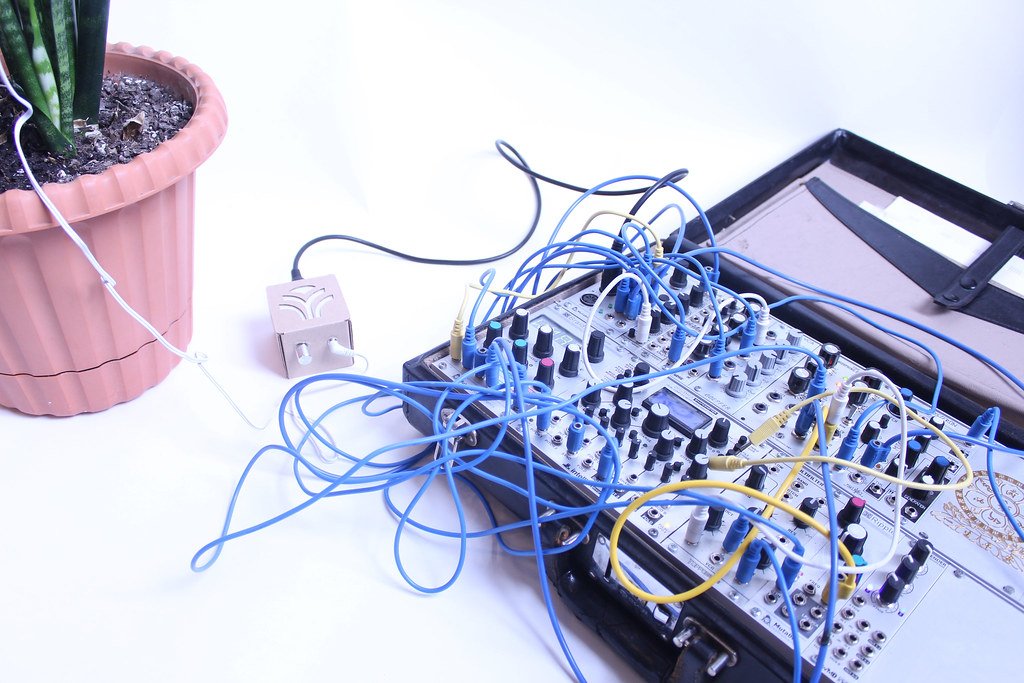

After Data Garden Quartet, the project took on a life of its own. We traveled to museums and festivals around North America, installing plants that played music. But everywhere we went, the reaction shifted from "Wow, look at that" to "How can I do that?"

Artists, musicians, and sound designers started reaching out, asking for the technology so they could incorporate plant bio-data into their own work. We realized that while we had built a beautiful installation, we had also inadvertently invented a new instrument.

The Reluctant Product Launch

I was initially resistant to making a hardware product. I had started Data Garden as a zero-waste record label because I hated the idea of manufacturing plastic that would eventually become waste. The thought of producing circuit boards and plastic enclosures felt like a betrayal of that ethos.

It was my friend and roommate, Jon Shapiro, who pushed me to see it a little differently. He argued that making a device was actually the best way to make this art accessible to more people and that we could do it with a bio-plastic enclosure that would help move the electronics industry into a more eco-friendly direction. We decided to call it MIDI Sprout per suggestion from our friend, Chris Powell.

Our friends, Gretchen and Thomas were the models for our MIDI Sprout campaign, which was shot in Sam’s living room. They’re now known as Carol and Cleveland Sings and make incredible music videos of their own.

We made a strategic choice to output MIDI rather than audio. We were brand new to making hardware products and we knew that the people who would buy this early version (the deep-diving MIDI nerds like us) were more likely to “RTFM” (Read the F%&$ Manual) and be patient with us as we refined the product. We weren't trying to make a consumer gadget and had no desire to. We were making a tool for artists.

The Kickstarter Struggle

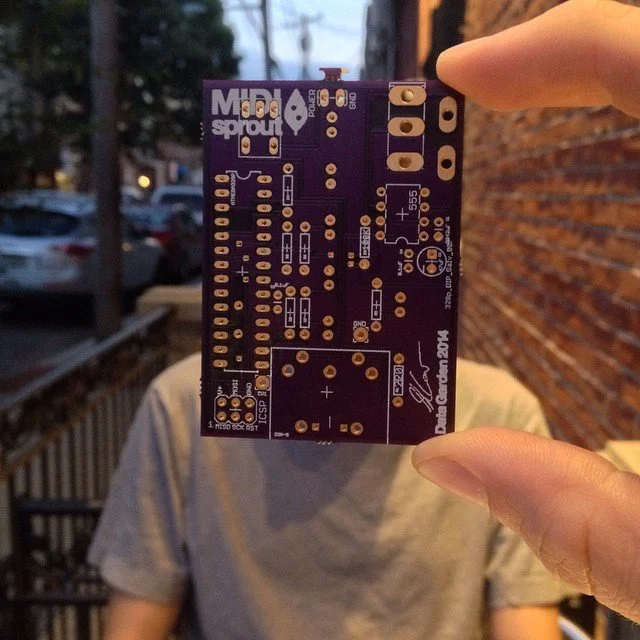

The first MIDI Sprout circuit board and the brain behind it (Sam), literally.

In 2014, we launched a Kickstarter and raised about $32,000. We sold the units for $100 each, thinking that was a fair price. We were wrong.

We quickly discovered that hardware manufacturing is incredibly expensive. Just creating the mold for the bio-plastic enclosure we envisioned was going to cost us $20,000, eating up more than half our budget before we even built a single circuit board. We realized the R&D alone had cost us a large portion of that $32,000. We had pre-sold units at a loss, we were two years late on delivery, and we were nearly bankrupt.

The stress was immense. We had $300 left in the bank, and angry backers were emailing us asking where their units were. It was during this pressure cooker period that my co-founder Alex Tyson decided to step away to focus on his film career.

The Cardboard Salvation

Jeremy, a MIDI Sprout backer, volunteered to produce the enclosures.

I felt burdened by the project, paralyzed by the cost of the bio-plastic enclosures. Then, a friend pointed out that Google had just released VR goggles made out of cardboard. She said, "Why don't you just put it in a cardboard enclosure?".

It was the perfect solution—sustainable, affordable, and distinct. A member of our Kickstarter community, Jeremy Helms, actually stepped up to design the enclosure for us. We held a pizza party at my house, and a group of friends helped hand-assemble 400 MIDI Sprouts using cardboard and Japanese craft paper for the light diffusers.

The Birth of a Community

We had fulfilled our Kickstarter promises, but we had about 60 units left over. We had no idea what they were actually worth.

The answer came when a guy tracked down my phone number and offered me $500 for a single unit. I was shocked. Shortly after, we took 10 units to Moogfest in Durham, NC. We priced them at $400—four times our Kickstarter price—and they sold out immediately.

When we listed the remaining 50 units online for $300, they sold out in 30 minutes, generating $15,000.

That moment saved the company. But more importantly, it proved that we weren't just selling a novelty. We were seeding a community. By stripping the device down to its rawest form—cardboard and circuitry—we attracted a core group of super-users who didn't just want to listen; they wanted to collaborate with nature. This wasn't just a product launch; it was the beginning of a global movement of artists co-composing with the natural world.