The Question – Can a Plant Play Music? (2012)

By 2012, Data Garden had established itself as a zero-waste record label, but we were about to pivot into something much stranger. The catalyst was an invitation from Anthony Smyrski to take over a space within his Megawords pop-up at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Originally, the museum just thought we might set up a little record shop to sell our plantable albums. But being in an art museum made us want to do something more impactful. We wanted to create a site-specific art installation.

It was my co-founder, Alex Tyson, who asked the question that would define the next decade of my life. He was deeply interested in early experiments regarding plant consciousness and bio-art, specifically the work of Cleve Backster and The Secret Life of Plants. He proposed a radical idea: Data Garden Quartet.

The Concept: Plants as Band Members

Alex’s vision was to create an installation where four different plants would play music together as a quartet. The initial musical concept was inspired by Terry Riley’s In C, where musicians are given different phrases and have the agency to select when to play them.

In this first iteration, we weren't trying to synthesize sound directly from the plants yet. Instead, Alex composed a series of beautiful synthesizer loops and phrases. The idea was to have sensors on the plants sending signals that would trigger these pre-recorded loops. As the plants shifted their activity, they would select different musical phrases, causing the composition to evolve over time.

The Hardware: A Hacked Lie Detector

To make this happen, we needed someone who understood electronics. We turned to our friend Sam Cusumano, who had built circuit-bent toys for our launch festival at Bartram's Garden. We knew Sam could build weird stuff, so Alex worked with him to design the circuitry needed to read signals from the plants.

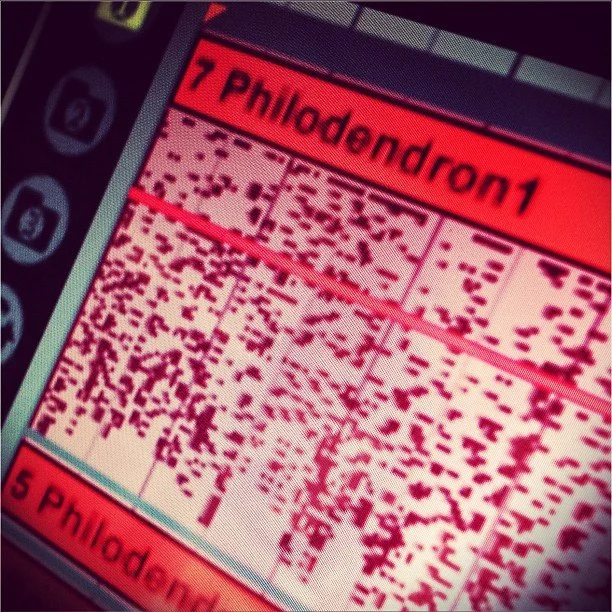

Sam’s solution was brilliant in its DIY simplicity. He built a makeshift sensor out of an old Radio Shack lie detector. This was based on the science of the polygraph—measuring galvanic impedance, or how electricity flows through the plant. Sam hooked this modified lie detector up to a computer running Pure Data (a visual programming language), which translated the wave from the plant into MIDI data.

The Architecture of Sound

My role was the engineering bridge. I had to take that stream of MIDI data coming from Sam’s lie detector and route it into Ableton Live to control the audio. I spent days building a system where the incoming data would trigger the specific loops Alex had composed.

It was a fascinating experiment. We had the hardware reading the plants, the software translating the language, and the "instruments" (the loops) ready to be played. Conceptually, it was solid. But as I sat there looking at the raw data Sam’s sensor was feeding into my computer, I noticed something. The data stream wasn't just a simple on/off switch; it was incredibly rich, filled with micro-fluctuations and constant activity.

We had built a system to trigger loops, but looking at that stream, I began to suspect that reducing this complex biological signal to a simple "play loop" command was leaving out the most interesting part of the story. If the plants were “speaking”, our translation system was only catching every tenth word.